My Aunt Jane is completely mad. (Rysmiel, when informed of this, said “Oh, you know!” in a deeply relieved tone.) She’s the kind of completely mad you get if you’re eighty-two and you have never actually grown up. She can’t walk, she says, only run or dance. She’s my grandmother’s first cousin, and so my first cousin twice-removed, and Zorinth’s first cousin three times removed, which is further away than most people actually keep counting kin. She came to lunch on Sunday, with one of her daughters (my second cousin once removed) and one of her grandsons (my third cousin, Zorinth’s third cousin once removed). The grandson and Zorinth didn’t actually communicate at all, despite, as my aunt put it, sharing three languages: English, French, and teenage grunting. I expect their children, who will be fourth cousins, which is where even my family stops counting kin, won’t really know each other. We had a pleasant if slightly manic late lunch. Then, at the time we were expecting them to go home, about six o’clock, she suddenly suggested that we all go to Porthcawl.

Porthcawl is a beach — well, a town, a seaside resort. It’s about twenty miles from here, and perhaps thirty from where she has always lived. She’s been going there for over seventy years. At first, she went for a month’s summer holiday by train, then a week by car, then eventually roads and cars improved sufficiently that she could drive there any time she wanted, and of course she wanted to all the time. When I was a child, and we’re talking thirty years ago, so she was in her fifties, she used to go there every warm day after school. (There are climates where this would make more sense.) She’s still doing it. She bundled us all up into cars, with towels and bathing costumes, because how could we say no, how could we let her out-run us, and off we went, to Porthcawl, skipping down the steep cliff path, and right into the sea for a vigorous game of water polo. (Actually I love water polo. I can’t run, but I can swim, so it’s the one ball game where I can still compete.) She outstayed both the teenagers in the water. When we came back up and got dressed under towels — at eight o’clock at night, still light but not very warm — she handed round a tin of biscuits. How like my childhood it was, shivering under a towel, tasting of salt all over, eating a biscuit. And how like Aunt Jane’s childhood it was, right down to the tin of biscuits. Who has a tin of biscuits any more? But they wouldn’t taste the same out of a packet.

It was while we were getting dry that she said they’d been down every day that week. Her daughter shrugged, in a way that said both “I can’t let my eighty-two year old mother out-run me” and “It’s easier to give in than argue”. And she’s marvellous, you know, for eighty-two, if she falls off a cliff in Porthcawl that would be exactly what she would want and much better than the ways most old people die, most of which she’s seen as she has had dancing partner after dancing partner die. She’s had a tragic life in many ways, losing her mother when she was born, her husband when she was pregnant with her son, and then losing that son when he was in his twenties. It’s not that none of it touched her, it did, but somehow it didn’t make a dent the way it does in ordinary people. Maybe it’s because she was brought up by Auntie Lyd, and Auntie Lyd kept right on bringing her up until Aunt Jane was in her fifties, and I suppose it was too late to grow up then, to learn to be responsible. She taught infant school children for years and years, and I expect she was very good at it. Absolutely marvellous, and still an enfant terrible. She wears people out, and doesn’t really notice, she just keeps bouncing along.

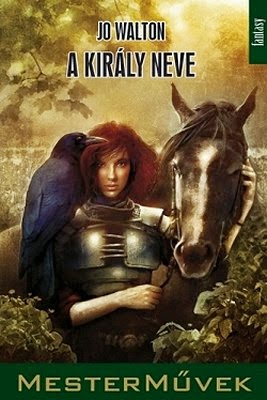

When AM proudly showed her The King’s Peace, a real published book written by our Jo, Aunt Jane looked at it, opened it, and read the first line. “What it means to be old is to remember things that nobody else alive can remember.” “That’s right,” she said, decisively, and shut the book and handed it back. On the other hand, when we left her on the beach on Sunday night, Zorinth said it was as if she hadn’t noticed that she wasn’t a teenager any more.