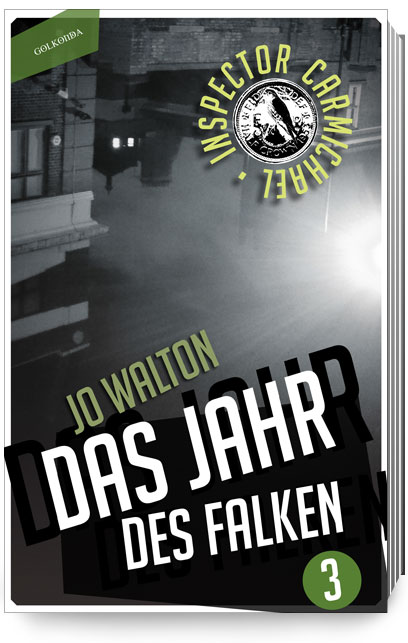

As you can imagine, cross-casting Shakespeare is something I’ve thought about a lot — in Ha’Penny, the female protagonist is an actress cast as Hamlet because cross-casting is this year’s fad in alternate history 1949.

Ursula Le Guin talked on Book View Cafe about her discomfort with Prospero cross-cast as female, and people have been addressing that as if she’d said something entirely different and much more gender-essentialist.

In some ideal future it might be possible to cast gender-blind. But now we bring our ideas about gender to texts full of Shakespeare’s ideas about gender, and when you switch a character’s gender everything changes, and sometimes it makes sense and sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes it says new things you didn’t at all mean to say. Sometimes it utterly shifts the balance. There are other things like this. You can’t cast Hamlet as an old old man or an eight year old, but you might get away with a fourteen year old. The text has a lot of give in it, but not infinite give. And when you change things, the world and the other characters change out from under you.

To take an extreme example, I think it’s quite clear if you look at Twelfth Night that it wouldn’t be possible to cross-cast only Viola. (Spoilers for Twelfth Night.)

Viola’s a girl castaway on a strange shore, who disguises herself in the clothes of the brother she thinks dead and gets a job as a page to the Duke, with whom she falls in love, and is sent by him to court Olivia, who falls in love with Viola while believing she’s a man. Putting an extra gender-twist in here would make it utterly stupid. Viola would have no need for disguise, she’d still have to hide her love for Orsino… (but then Sebastian is openly bi, why shouldn’t he/she be? Unless homosexuality is what Antonio has been banished for, which it could be…) And think of the duel scene. Viola has to stay female for the plot to work.

What you need to do to make it work with a male Viola is cross-cast everyone. And if you do that, if you gender-switch everyone in the play, you change it from a world where men have agency and can do things and women can’t to a world like Wen Spencer’s A Brother’s Price where it’s the other way around.

If it were Amazon Illyria they washed up in, with Oliver waiting to be wooed and Orsina wooing him, with women active and men passive, the characters that are most changed aren’t any of the lovers but the comic relief.

Maria, Olivia’s maid, is saucy and bawdy and the main instigator of the Malvolio plot. Sir Toby and Sir Andrew and Feste are moved by her. If you reverse them, you have a very interesting and not very nice Mario, moving… gosh, comic relief drunken older women. How strange they would be! How unfunny we would find them. What a world this is! It’s the world of Vonarburg’s In The Mother’s Country or Tepper’s The Gate to Women’s Country. As soon as I think about it, it becomes one of those “nasty rough men outside the walls” stories, although the men we see, the ones who Shakespeare made women, are gentle and passive, all but Maria/o. We’re inside the walls and the civilized women and gentle pampered are all we see… and disguised Viola, man into woman, continuing to mess with people’s gender-expectations… but their presence implies dangerous rough men outside. Doesn’t it in the original? They were there, in other worlds of Shakespeare. He knew they existed. He didn’t call them here.

It’s always an interesting thought experiment.