The Just City is the first of a three book series, followed by The Philosopher Kings, and Necessity. The series as a whole is called “Thessaly”.

The Just City was published by Tor in North America on January 13th 2015, and as an e-book from Corsair in the UK on February 28th, with Corsair’s paper edition following in July. The Philosopher Kings was published by Tor in North America on June 30th 2015, with a simultaneous UK e-book, and UK paper book in July 2016. Necessity was published by Tor on July 12th 2016. All three books were also simultaneously released as audiobooks from Audible, narrated by Noah Michael Levine, on July 12th 2016.

The Just City was nominated for the Prometheus Award.

Tor’s back cover copy:

“Here in the Just City you will become your best selves. You will learn and grow and strive to be excellent.”

Created as an experiment by the time-traveling goddess Pallas Athene, the Just City is a planned community, populated by over ten thousand children and a few hundred adult teachers from all eras of history, along with some handy robots from the far human future—all set down together on a Mediterranean island in the distant past.The student Simmea, born an Egyptian farmer’s daughter sometime between 500 and 1000 A.D, is a brilliant child, eager for knowledge, ready to strive to be her best self. The teacher Maia was once Ethel, a young Victorian lady of much learning and few prospects, who prayed to Pallas Athene in an ungaurded moment during a trip to Rome—and, in an instant, found herself in the Just City with grey-eyed Athene standing unmistakably before her.

Meanwhile, Apollo—stunned by the realization that there are things mortals understand better than he does—has arranged to live a human life, and has come to the City as one of the children. He knows his true identity, and conceals it from his peers. For this lifetime, he is prone to all the troubles of being human.

Then, a few years in, Sokrates arrives—the same Sokrates recorded by Plato himself—to ask all the troublesome questions you would expect. What happens next is a tale only the brilliant Jo Walton could tell.

That’s “the brilliant Jo Walton” as opposed to the dumb everyday Jo Walton that’s all I have to work with…

In a way, this is the first idea I ever had. People ask me where I get my ideas from, and surprisingly often the answer is “From reading other things”. I had the original idea for Thessaly when I was fifteen and first read Plato’s Republic. The original idea was “But what would happen if you tried this with real ten year olds?” (Indeed, a form of this original idea is discussed in Among Others.) A version of this story was the first complete novel I ever wrote. I think it was fifty thousand and one words long. I wrote it on a typewriter — actually I wrote the first draft longhand and then typed it. It took forever — that is, it took all of a summer school holiday, during which I don’t remember doing anything but writing it. It had time travellers, Plato’s Republic, love, and Ficino. It didn’t help that at sixteen I didn’t know half enough about either love or Ficino… never mind how to write. I learned a lot about how to write from writing it, but it was objectively awful and you can be glad that I don’t still have a copy. Having written it, and made it as good as I could at the time, I naturally sent it off to publishers who, unsurprisingly, rejected it, and that was that. I went on to write other things, and grow up, and gave up writing, and started again, and so on. I didn’t ever reconsider this story — I was done with it. I have never been able to go back to ideas I’ve messed up, and also I had a lot of other ideas. I’d remember it every time I read The Republic, and every time I had a conversation about The Republic. And sometimes I’d think, you know, it’s a pity I messed that up because it was a good idea. But ideas are the easy bit, and that was it.

Then last year, half way through writing My Real Children, I was reading Ada Palmer’s brilliant Ex Urbe post Was Machiavelli an Atheist? In the comments she quotes Socrates, and it reminded me it was ages since I’d read The Apology. So I read it, and afterwards I was reading the Crito, and I had to go to the accountant, and I was walking along Rene Levesque downtown thinking “If I was Crito I’d have hit Socrates on the head and dragged him out of Athens and let him argue later when he woke up in Thessaly…” and I suddenly remembered my old time-travel/Republic story and realised, between one step and the next, that what it needed, what it had always needed, was to be fantasy and have Greek gods in it, and then it could have Socrates. Socrates in the Republic, horrified at what Plato had done in his name. And of course the other thing it needed was Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne and a theme that revolved around volition. And just like that it wasn’t a dead idea any more, it was a live and writhing idea, and I wanted to rush home and write it right away. But I didn’t, because I also wanted to finish MRC. So I finished MRC, as fast as I’ve ever written anything, and went straight on to write TJC without any gap in between. I wrote it bertween 23rd April and 12th June 2013, in 28 writing days (I lost a week to Wiscon, where I read the first chapter aloud). I then spent the rest of 2013 writing The Philosopher Kings, and then a considerable amount of January and February of 2014 revising TJC and writing six additional chapters. So it took me two months to write and two months to revise… or if you want to look at it another way, it took me more than thirty years. In that thirty years I’d had time to read up on Ficino, and I think I figured out some things about love as well, though that’s still a work in progress.

Then last year, half way through writing My Real Children, I was reading Ada Palmer’s brilliant Ex Urbe post Was Machiavelli an Atheist? In the comments she quotes Socrates, and it reminded me it was ages since I’d read The Apology. So I read it, and afterwards I was reading the Crito, and I had to go to the accountant, and I was walking along Rene Levesque downtown thinking “If I was Crito I’d have hit Socrates on the head and dragged him out of Athens and let him argue later when he woke up in Thessaly…” and I suddenly remembered my old time-travel/Republic story and realised, between one step and the next, that what it needed, what it had always needed, was to be fantasy and have Greek gods in it, and then it could have Socrates. Socrates in the Republic, horrified at what Plato had done in his name. And of course the other thing it needed was Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne and a theme that revolved around volition. And just like that it wasn’t a dead idea any more, it was a live and writhing idea, and I wanted to rush home and write it right away. But I didn’t, because I also wanted to finish MRC. So I finished MRC, as fast as I’ve ever written anything, and went straight on to write TJC without any gap in between. I wrote it bertween 23rd April and 12th June 2013, in 28 writing days (I lost a week to Wiscon, where I read the first chapter aloud). I then spent the rest of 2013 writing The Philosopher Kings, and then a considerable amount of January and February of 2014 revising TJC and writing six additional chapters. So it took me two months to write and two months to revise… or if you want to look at it another way, it took me more than thirty years. In that thirty years I’d had time to read up on Ficino, and I think I figured out some things about love as well, though that’s still a work in progress.

![Vincenzo Foppa [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4f/The_Young_Cicero_Reading.jpg)

Cicero Reading, 1464

Thessaly has more direct and obvious influences than many of my books. Plato, of course, and Xenophon, and Homer and the Homeric hymns and my general love of the whole classical thing. (I say I am a Romano-Briton, a Celt who loves the civilization of the Middle Sea, and I think this is something that comes out in quite a bit of my work.) I first came to know the classical world enough to fall in love through reading the historical novels of Mary Renault — and it was Mary Renault’s The Mask of Apollo and The Last of the Wine that led me to reading Plato. Then later, on a wet Friday afternoon in 1981 my Latin teacher, N.D. Evans, told me about Ficino and the Renaissance. I realised recently that it was also influenced in its original conception by Philip Jose Farmer’s Riverworld books, which mix together everyone who ever lived on the banks of an endless river. Most importantly there’s Ada Palmer, who has been mentioned on this page before, and to whom Thessaly is dedicated. Her contribution, both direct and indirect, is immeasurable. She introduced me to Florence and to Bernini, she often had the exact piece of information I needed just when I needed it as I was writing, and her suggestions during revision were invaluable. Beyond all that my book was directly influenced in several ways by my having read her wonderful Terra Ignota series which begins with Too Like the Lightning — which will, through the vagaries of publishing, not come out until after The Just City (look for it from Tor Summer 2016). As if that wasn’t enough, her music is also inspirational as well as being amazing.

The Just City is my eleventh novel.

First three chapters on Tor.com

Goodreads Page for The Just City

Brilliant, compelling, and frankly unputdownable.

Romantic Times Top Pick Review

Walton is not only an amazing writer, she’s an amazing writer who almost never does things the same way twice. The Just City is a delight, both playful and intellectually rigorous.

Library Journal Starred Review

As skilled in execution as it is fascinating in premise, Walton’s new work doesn’t require a degree in classics, although readers might well be inspired to read Plato after seeing the rocky destruction of his dream. Although rich with philosophical discussions, what keeps this novel from becoming too chilly or analytical are its sympathetic female characters.

Booklist Starred Review

A remarkable novel of ideas that demands—and repays—careful reading. It is itself an exercise in philosophy that often, courtesy of Socrates, critically examines Plato’s ideas. If this sounds abstruse, it sometimes is, but the plot is always accessible and the world building and characterization are superb. In the end, the novel more than does justice to the idea of the Just City.

simply by writing what interests her, she produces such powerhouses as The Just City.

Not something you come across every day.

Nobody writes like Walton.

The Just City is a glorious example of one of the primary purposes of speculative fiction: serving as a map to the potentials and miseries of a possible world. But it is also a map that should be scrawled with the words, “here be dragons.”

Frequently Asked Questions

Q. All yout books are different from each other!

A. Yes, I’ve noticed that myself.

Q. Do I have to have read Plato to understand this book?

A. No, not at all. I’ve tried hard to make it accessible to a reader with no prior knowledge.

Q, If I have read Plato will I find it laughably simplistic?

A. I hope not. I tried hard to make it interesting for a reader with lots of prior knowledge.

Q. How did you get the idea?

A. Plato wrote about setting up an ideal society and starting with ten year olds, who would be taught music, mathematics and gymnastics and trained in rhetoric and…

Q. Are we there yet?

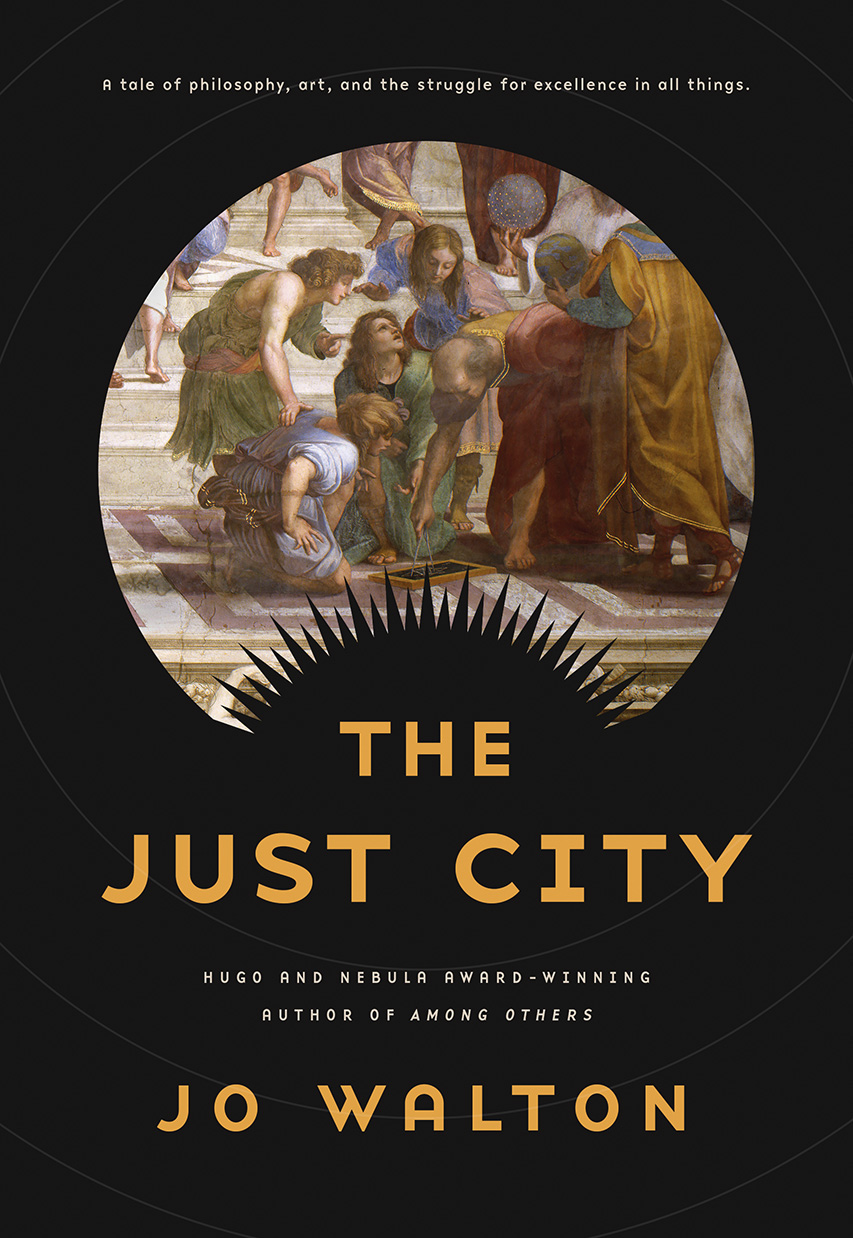

A. And so that’s where I got the idea from. Look at that bit of School of Athens. Some of the kids are totally paying attention and looking at the diagram. I think because I was a teenager when I first read the Republic and had the idea, I remembered very clearly that ten years olds are not empty vessels.

Q. What’s in this from the original version?

A. Nothing. Not a single word. The original version was destroyed in the early eighties when I was in Greece.

Q. It was still in your head, right? So what’s in it from the original version?

A. Simmea, though she wasn’t called that. Ficino. The idea that real people would mess up all Plato’s neat ideas, especially with regard to love and sex. Time travel, and the idea of rescuing all the lost things of the ancient world. Kind of the shape, though only partly. I don’t think any of the scenes are the same. The second half of the original version was a complete mess.

Q. Why did you break the story into parts? Did you just want to sell more copies?

A. If The Philosopher Kings was the second part of the same story, and if it started two seconds after the end of the Last Debate, I’d have made it one book. It is in fact a separate story set twenty years later. Necessity is set forty years after that. This is in fact that old fashioned thing, a generational saga.

Q. When in history is the city founded?

A. Before the Thera eruption. Before the Trojan War.

Q. How plausible are the robots?

A. Robots are exploring the solar system at this very moment. And in Australia they’re milking cows and mining. The Workers are supposed to come from about fifty years ahead of now, so yes, I think they’re plausible enough.

Q. Where can I find the poem Submersible Moonphase?

A. Right here.

Q. What are the other things you quote from?

A. Plato’s Crito, Mary Renault’s The Last of the Wine, and Ada Palmer’s Dogs of Peace

Q. Does The Philosopher Kings have start quotes?

A. Why, yes. They’re from Ficino’s Letters, Pico’s Oration, Elizabeth Von Arnim’s The Enchanted April, and Ada Palmer’s Somebody Will.

Q. How about Necessity? I bet that has start quotes too, huh?

A. Yes. They’re from Keats, Ovid, Plato’s Euthyphro and Ada Palmer’s A New World.

Q. What did the Masters have to do to get to the Just City?

A. Read the Republic in Greek and pray to Athene to help make it real.

Q. Reading it in English wouldn’t count?

A. No. It has to be in Greek not in any vernacular translation — this lets them all have Greek as a common language of communication once they’re there.

Q. So I have to read it in Greek and then pray to Athene?

A. You do know this is fiction, right?

Spoiler questions after the giant cover!

Q. Who are the narrators of the later books?

A. PK has Apollo and Maia exactly the same, but the other narrator is Simmea’s daughter Arete. (“My mother is a philosopher and my father is a very philosophical god, so naturally they named me Arete, which means excellence.”) Necessity has Apollo, Simmea’s grand-daughter Marsilia, a silver called Jason who works on a fishing boat, and Crocus.